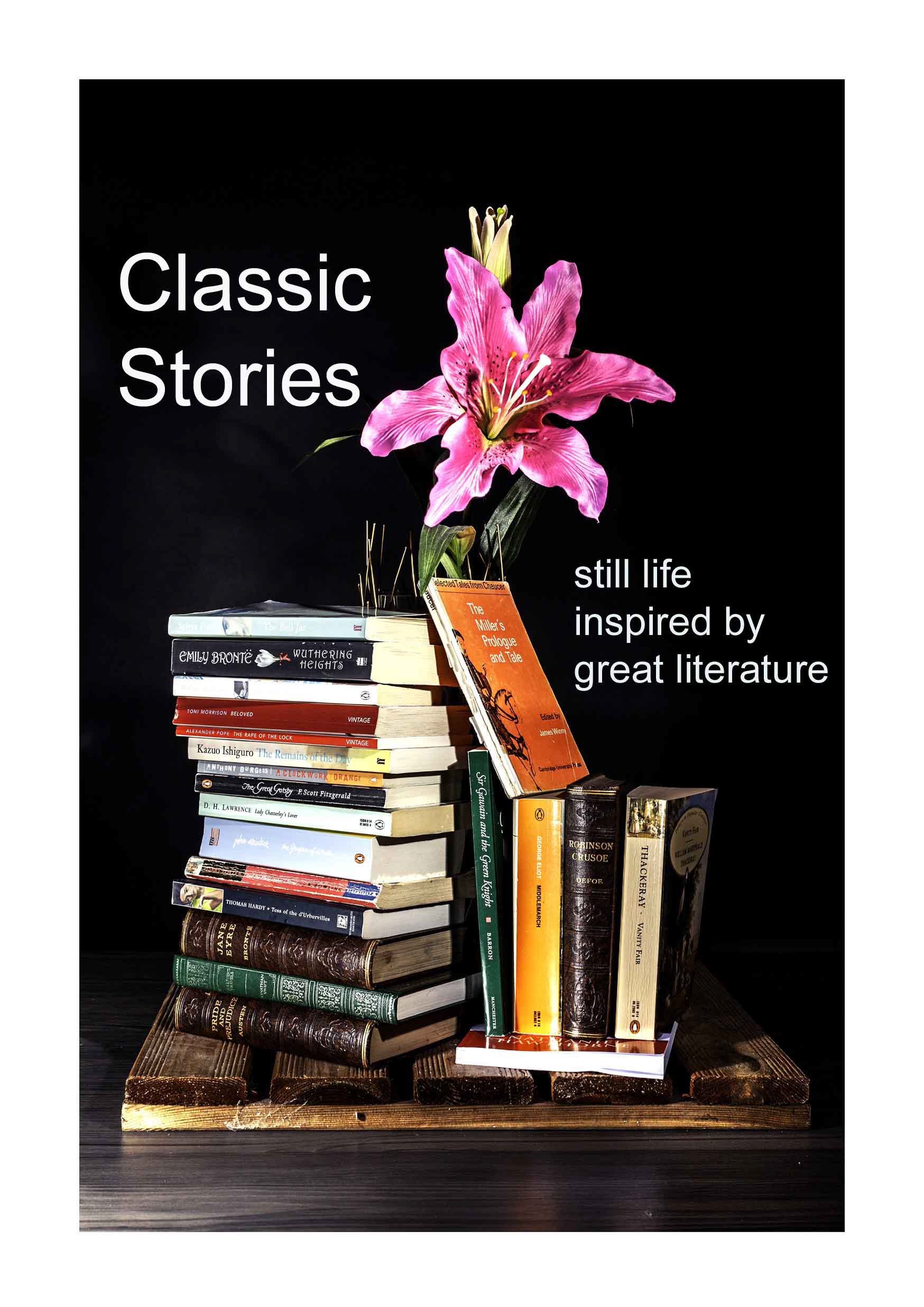

Imagery, symbol and metaphor - when graphic descriptions of sex were not acceptable.

Tess of the d'Urbevilles and Lady Chaterley's Lover

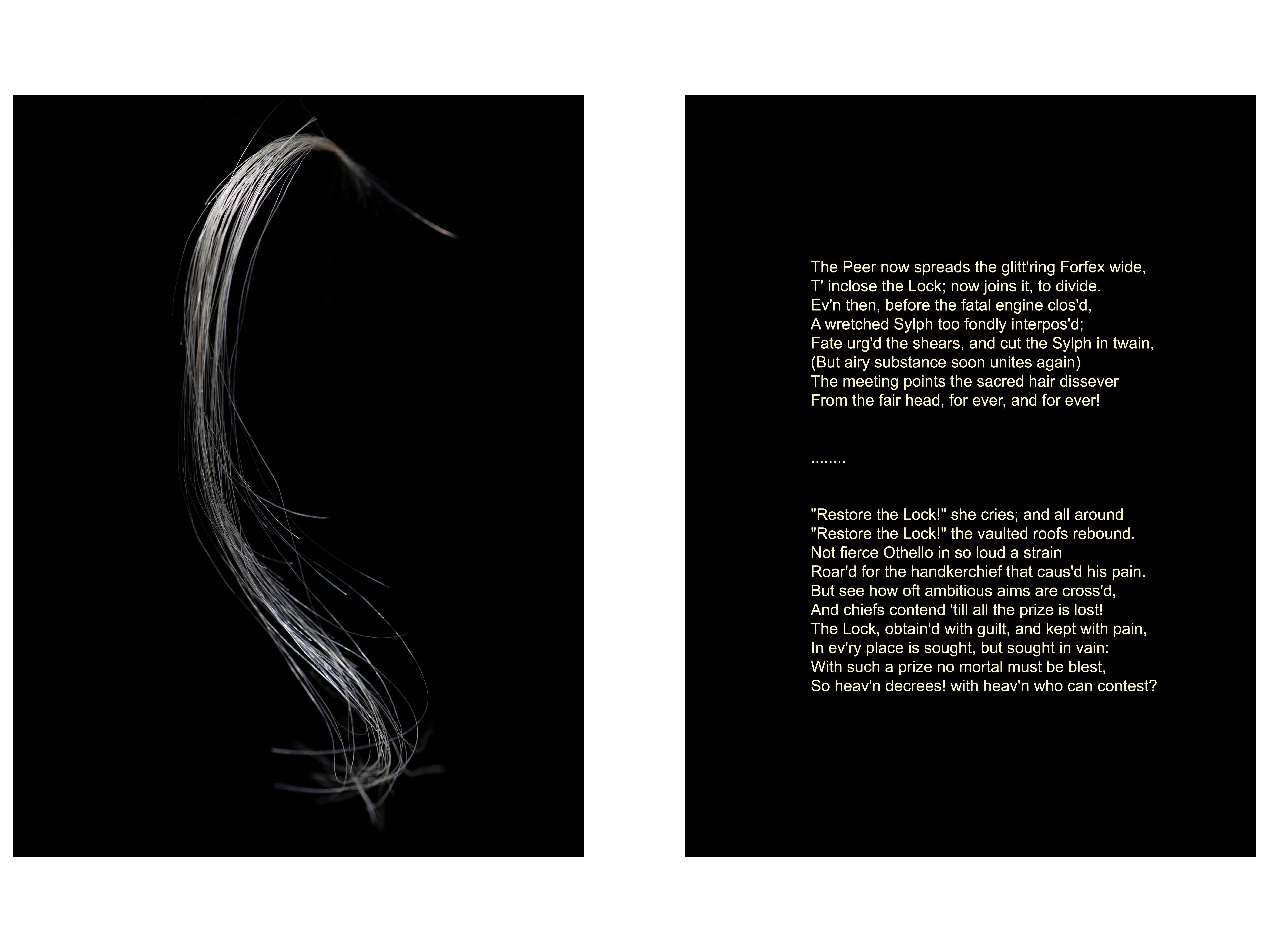

Tess, a working class ‘cottage girl’, is seduced by the dissolute, aristocratic Alex d'Urberville. The novel was published in 1892, in the final decade of the Victorian era, when explicit reference to sexual activity in literature was, in most cases, avoided, or done obliquely, via metaphor and innuendo. This passage from the Tess of the D’Urbevilles comes several chapters before the seduction scene, which Hardy deals with using generalisations rather than detail:

He conducted her about the lawns, and flower-beds, and conservatories; and thence to the fruit-garden and greenhouses, where he asked her if she liked strawberries.

“Yes,” said Tess, “when they come.”

“They are already here.” D’Urberville began gathering specimens of the fruit for her, handing them back to her as he stooped; and, presently, selecting a specially fine product of the “British Queen” variety, he stood up and held it by the stem to her mouth.

“No—no!” she said quickly, putting her fingers between his hand and her lips. “I would rather take it in my own hand.”

“Nonsense!” he insisted; and in a slight distress she parted her lips and took it in.

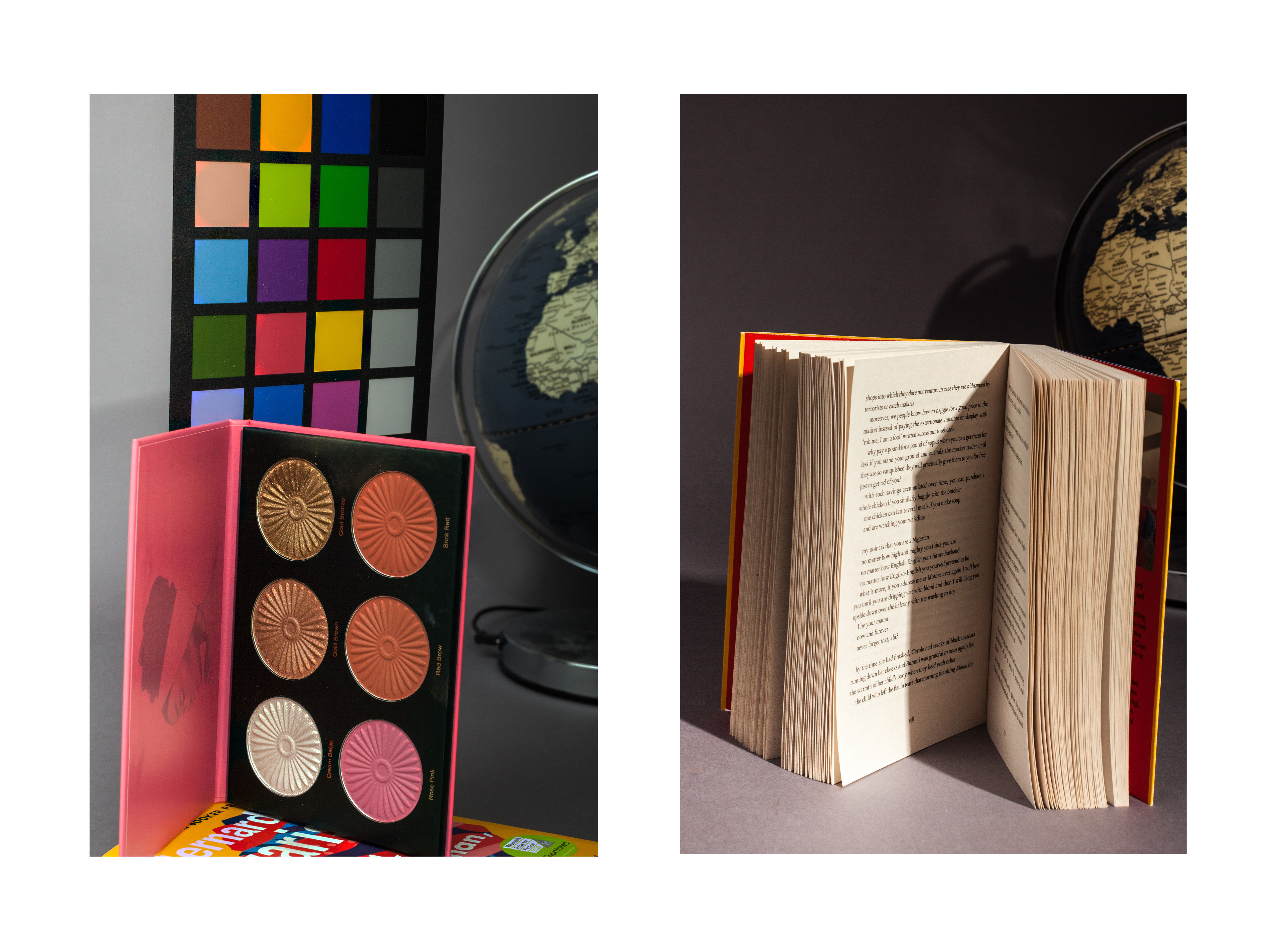

A generation later, in 1928, the social-class tables are turned in D H Lawrence’s novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The man is Mellors, a working class gamekeeper, and the woman an aristocrat, Lady Constance (Connie) Chatterley, already married to a man who has been crippled during World War One.

Lawrence describes details of the sexual affair between Mellors and Lady Chatterley in graphic, explicit detail. Such was the concern – outrage – about the language and the content, that Lawrence could not find a publisher for his book in the UK.

When it was eventually published, in 1960, the publishers, Penguin Books, had to face an obscenity trial.

Penguin Books won the case. The Chatterley trial became a landmark case in publishing. The swinging sixties had begun.