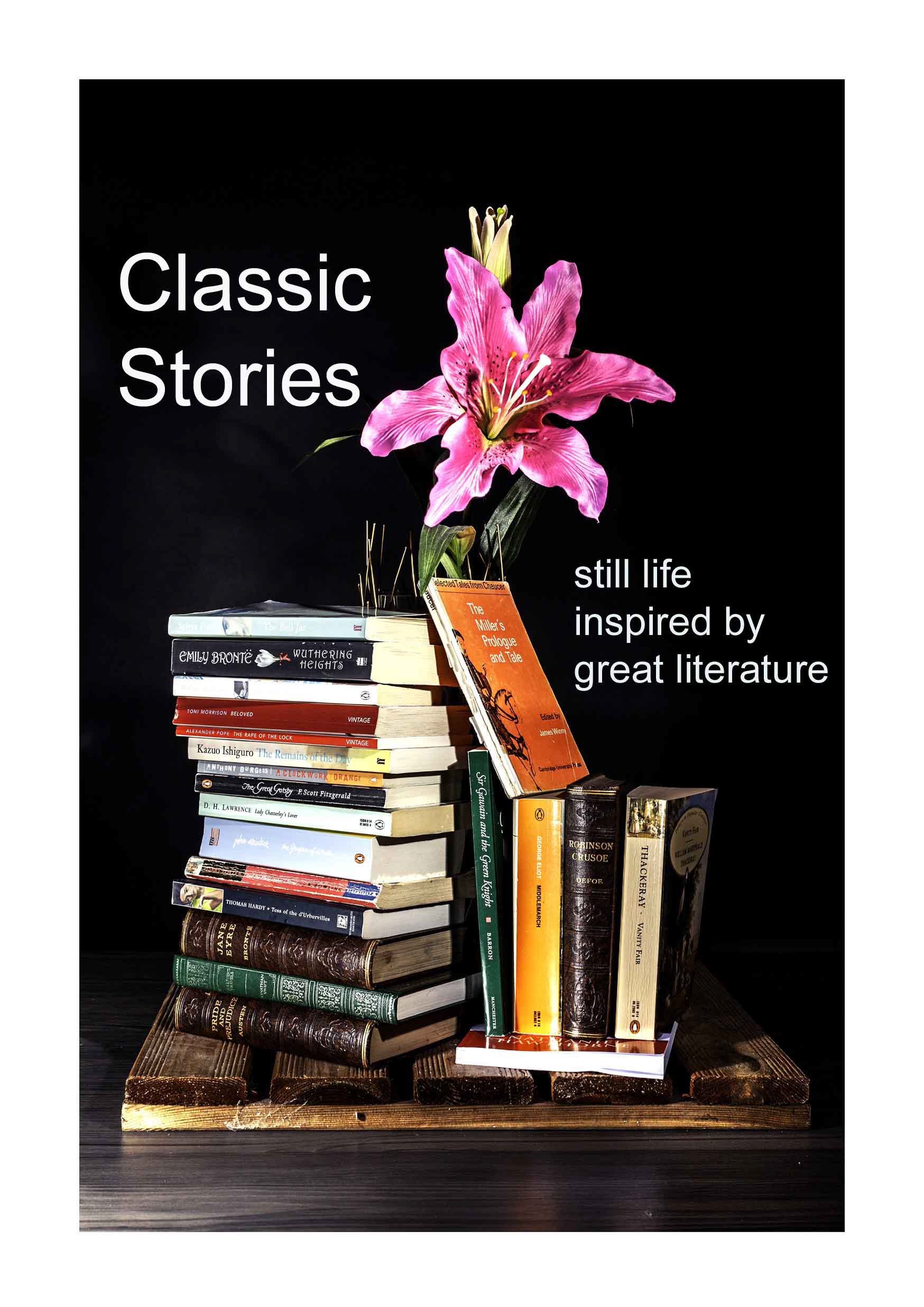

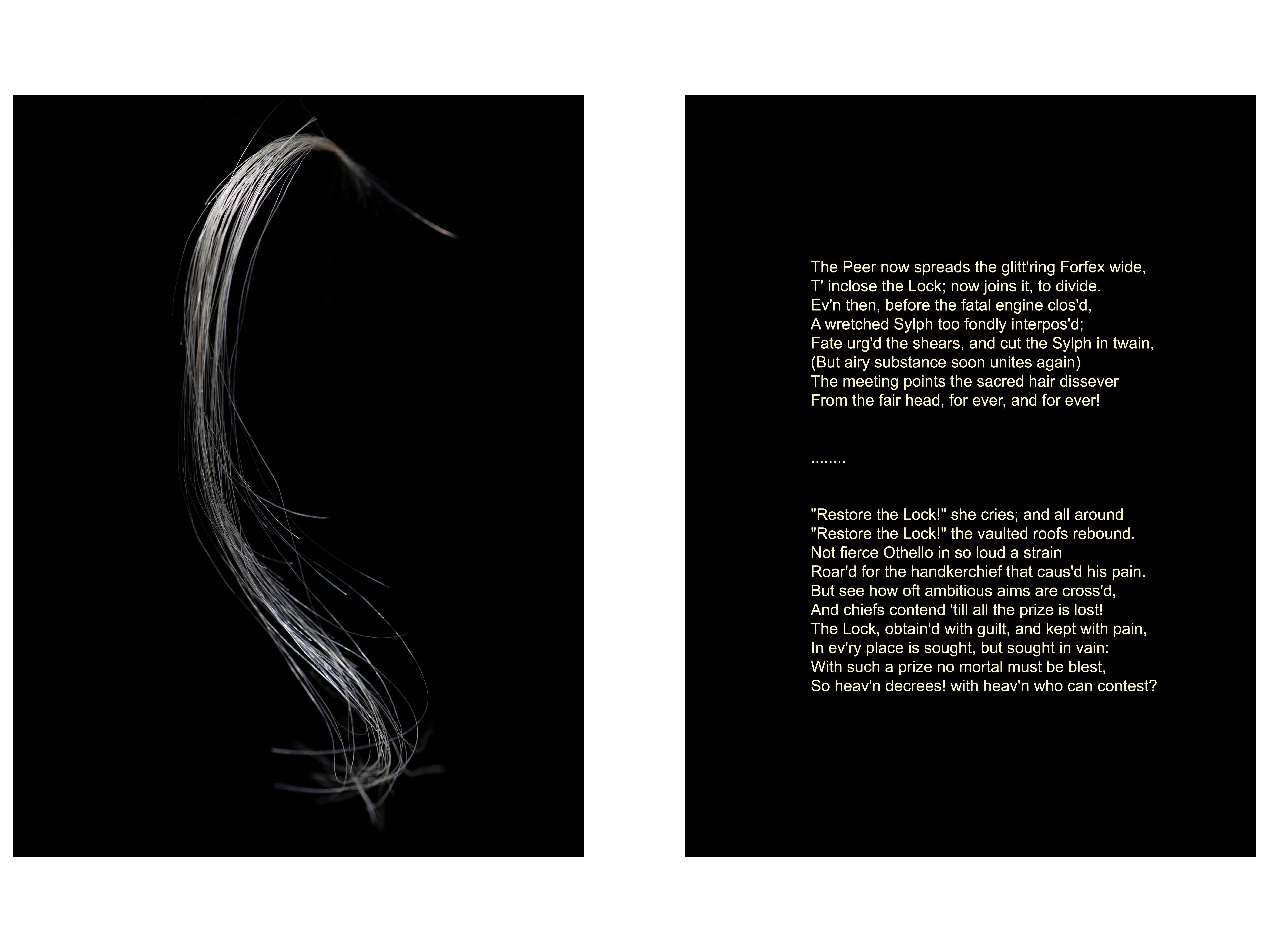

In The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer, writing around 1390, joins a fictional group of travellers on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Thomas à Becket at Canterbury Cathedral, to give thanks that they had survived the winter. The pilgrims come from all walks of life – several different occupations and classes of society are represented.

Each pilgrim is asked to tell a story. Chaucer’s first two story-tellers, the Knight and the Miller, are quite different in social background, and their stories reflect this, in content, and in style.

The Knight begins the tales with a very moral story about Palamon and Arcite, imprisoned together, but obsessed with the same woman. Each vows to woo her on their release. It’s a tale of high moral values, courtly behaviour, gallantry and dignity in rivalry. The same story is told by Shakespeare in his play The Two Noble Kinsmen.

The Miller then tells his tale – and what a tale it is! It’s little more than a crude, bawdy joke in which a crafty academic plots the seduction of Alison, the beautiful wife of his slow-witted landlord, John the carpenter. Alison is a willing accomplice to this seduction, but another man, Absalon, the local parish clerk, also wants to seduce Alison. He loses out to Nicholas and as revenge, he goes to the local blacksmith, picks up a red-hot makeshift branding iron and leaves his mark on Nicholas’ bare bottom, having previously had to suffer a flatulent gust in the face from Nicholas:

“This Nicholas anon leet flee a fart,

As greet as it had been a thonder-dent..”

Whereas the Knight tells his story of love with restraint and reserve, the Miller tells his crude tale with all the relish of a lecherous drunkard. His description of the Carpenter is over in just two lines. His description lingers on the physical appearance of Alison for thirty-eight lines.

Chaucer’s storytelling skills are evident in the variety of tales, and in the variety of storytellers that he uses to entertain the reader.