++ Trigger Warning: contains frequent anti-semitic references

++ Trigger Warning: contains derogatory comments about people of colour

++ Trigger warning: contains racist jokes aimed at German, Scottish, French and English men

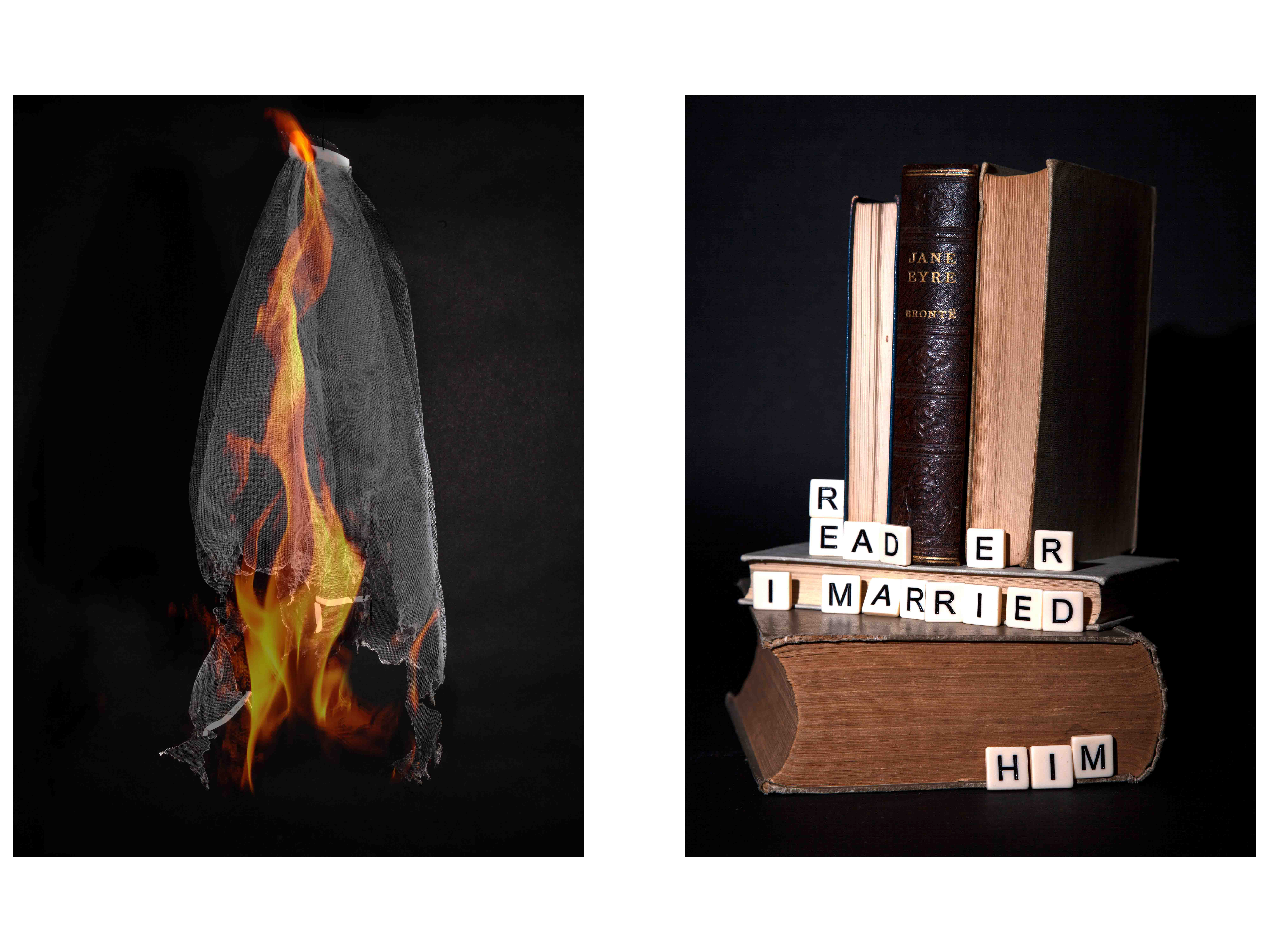

++ Trigger warning: contains threatening behaviour involving the cutting out of someone’s heart with a dagger in a courtroom.

++ Trigger warning: contains a plethora of sexist attitudes

So might a modern day theatre production of The Merchant of Venice be prefaced. Several of Shakespeare’s plays contend for a place on the ladder in the Cancel Culture era, but The Merchant of Venice is the Manchester City of that league table.

Nevertheless, The Merchant of Venice is, in many respects, a brilliant play that interweaves two disparate plots, one of love, one of revenge, both cleverly addressing the role of wealth in a society steeped in risk-taking and financial uncertainties – in other words, in gambling for very high stakes. It is a play that discusses what we do value, and what we should value.

The presentation of intolerant and racist attitudes, particularly but not exclusively amongst the men, is a lesson for our age. Three of the women, Jessica, Nerissa and Portia, need to dress up as men in order to effect their plans. Portia is the star of the play – one of Shakespeare’s most resourceful, intelligent and humane female characters. Her courtroom confrontation with Shylock culminates in the ‘Quality of Mercy’ speech, a beautiful and uplifting expression of human kindness that ought to be compulsory reading for all who weald power over less fortunate humans. It is the story that has given us the phrase ‘a pound of flesh’ – a metaphor that describes legally just but ethically unjust deserts

Our social-media saturated current age oscillates between benign sensitivity and virtue-signalling outrage. The Merchant of Venice may not survive its sometimes rightful and often self-righteous scrutiny. Though public performances of the play may become less frequent, perhaps in the future we will value works of art as products of their fault-ridden era that have survived to be studied, analysed, and perhaps even enjoyed, in our own differently fault-ridden era.