It’s difficult picking a single image that crystallises the novel Middlemarch, by George Eliot – (her real name was MaryAnn Evans).

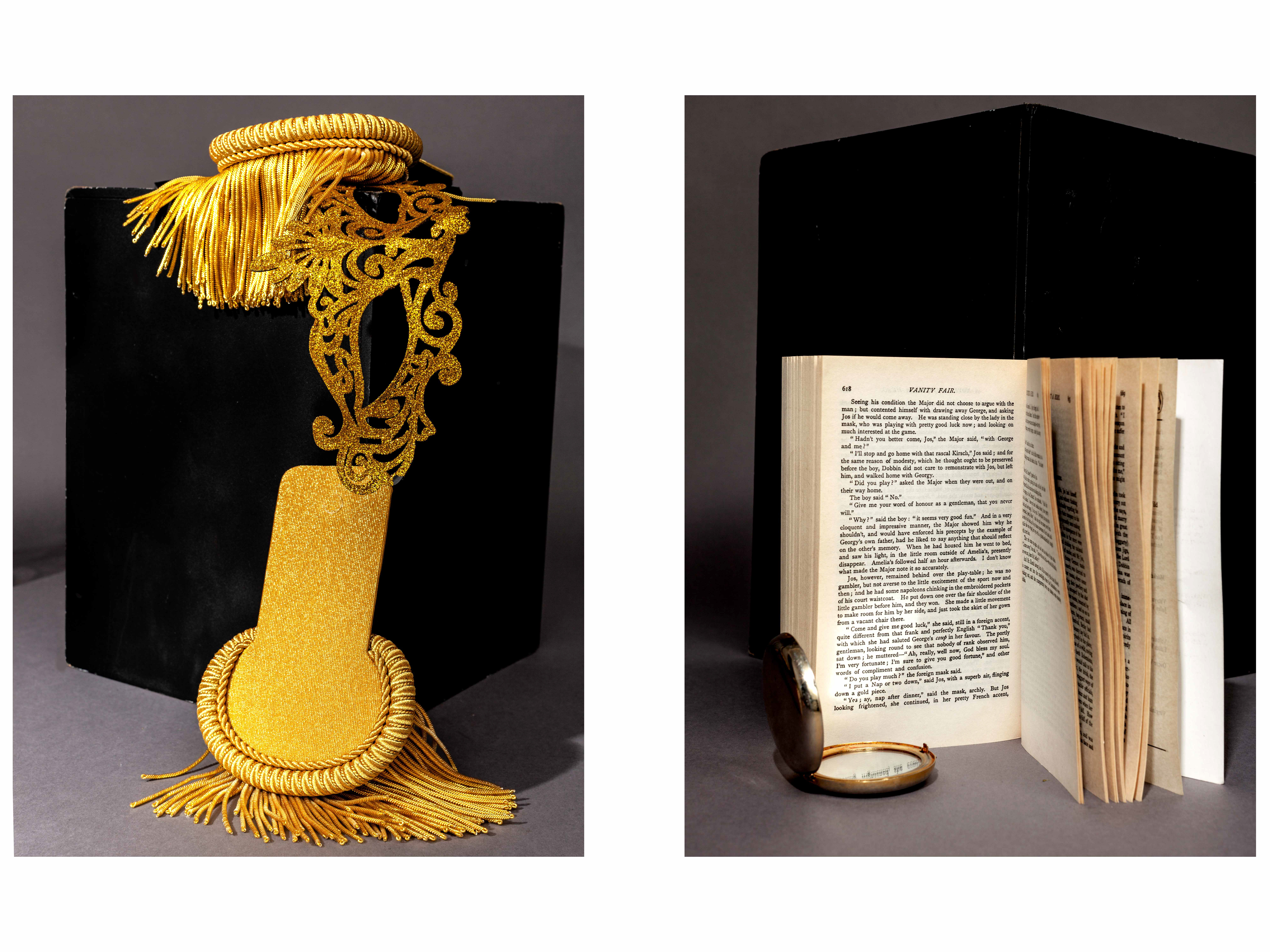

The Last Will and Testament plays a part in two of the narrative threads. Fred and Mary hope to inherit some wealth on the death of Mr Featherstone, but he has confusingly left two wills, and his money and land all go to a distant relative, thereby confounding the two young hopeful lovers..

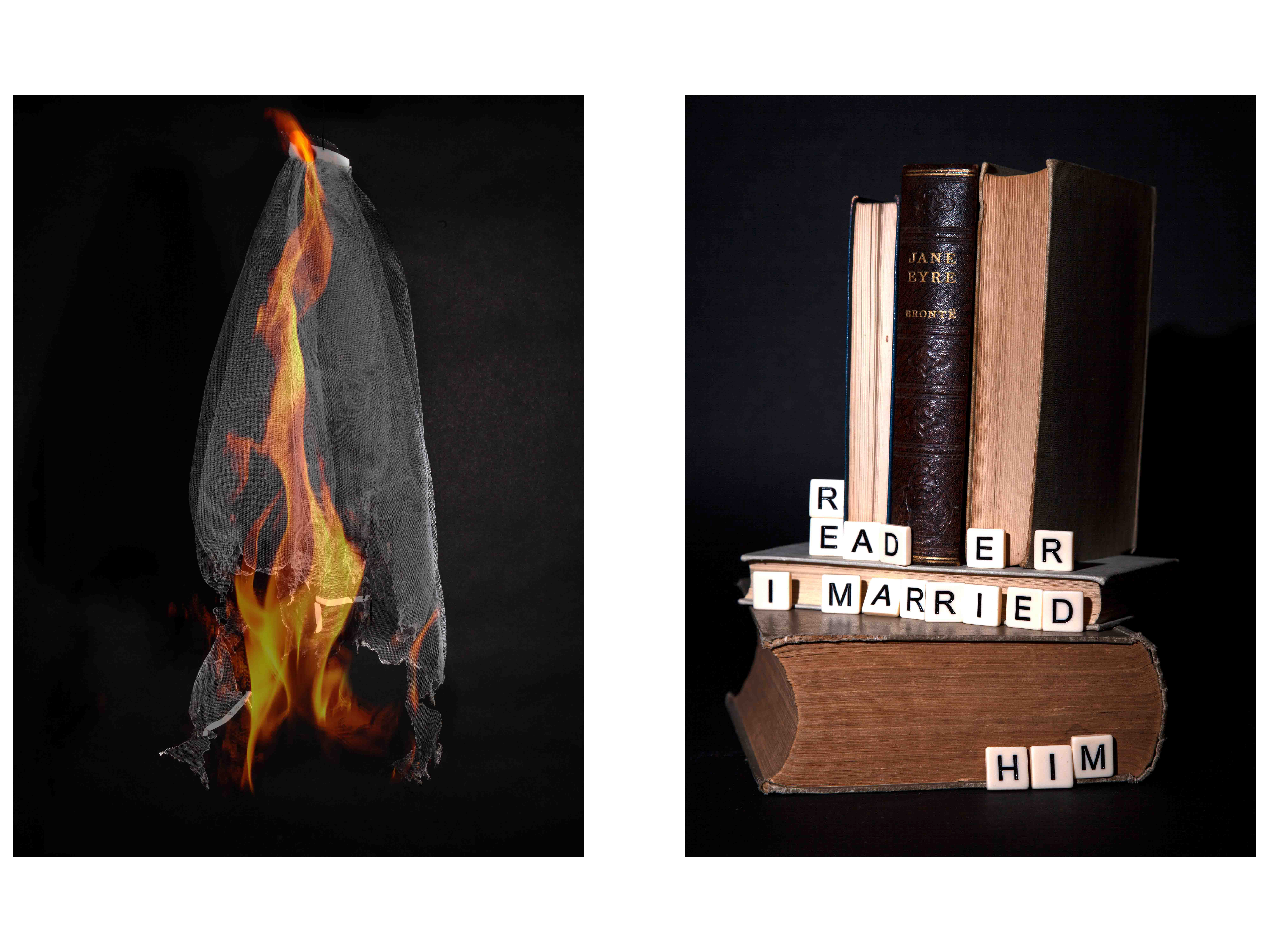

In another thread, Dorothea Brooke, one of the great heroines of literature, marries a decrepit academic, Casaubon, whose selfishness is evident during his life and continues after his death. His last will and testament insists that Dorothea will forfeit all of her inheritance if she ever marries the real love of her life, Will Ladislaw.

But the brilliance of this book comes not in the narratives and their outcomes but in the commentary that Eliot provides for the reader, helping us with her incisive and razor-sharp mind to move from the particular to the general, so that we can relate these fictional events to our own lives.

There are countless examples of this omniscient commentary, one of the best of which is in the final lines of this lengthy, worthy novel:

But we insignificant people with our daily words and acts are preparing the lives of many Dorotheas, some of which may present a far sadder sacrifice than that of the Dorothea whose story we know.

Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.